Lorraine Hansberry

To Be A Leader In Turbulent Times

In 1930, Amos N’ Andy was one of the most popular radio programs in the nation. People across America were entranced by the storyline, which began with Amos Jones and Andy Brown leaving a farm in Atlanta to head for Chicago. Despite warnings from a friend, they purchased tickets and ham-and-cheese sandwiches for $24 and went in search of a better life. The radio show ran until 1960, during which time listeners enjoyed storylines about various the antics of naive Amos, lazy Andy, and a full cast of distinctive characters. By 1931, over 40 million listeners tuned in and the show became the highest rated radio comedy in history.

In 1930, Amos N’ Andy was one of the most popular radio programs in the nation. People across America were entranced by the storyline, which began with Amos Jones and Andy Brown leaving a farm in Atlanta to head for Chicago. Despite warnings from a friend, they purchased tickets and ham-and-cheese sandwiches for $24 and went in search of a better life. The radio show ran until 1960, during which time listeners enjoyed storylines about various the antics of naive Amos, lazy Andy, and a full cast of distinctive characters. By 1931, over 40 million listeners tuned in and the show became the highest rated radio comedy in history.

Lorraine Hansberry was born into an America where most of the white population experienced black culture primarily through the lens of white men wearing the audio version of “blackface.” Her life would illustrate just how little Gosden and Correll really knew about the people they were portraying.

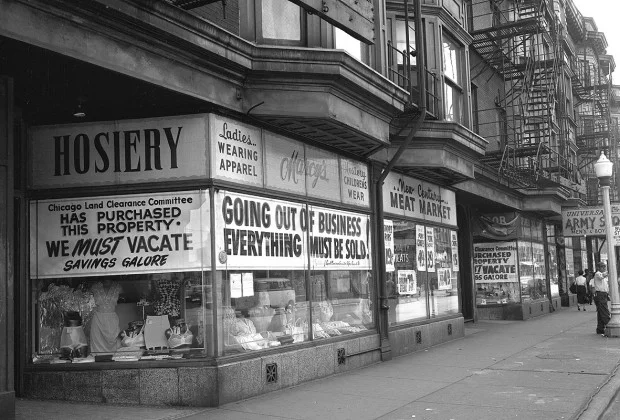

Hansberry was born in Chicago, Amos and Andy’s own home, on May 19,1930 as the last of four children. Chicago was plagued by the nation’s depression as well as by a seemingly endless stream of the country’s worst gangsters and a local government too weak or too corrupt to address the problems. Chicago was one of the most racially segregated cities in the country, but was experiencing a “great migration” of African Americans who were promptly packed into a “Black Belt” full of claustrophobic, squalid housing developments that were so dangerous hundreds of people burned alive in fires every year.

The streets were hardly safer than the houses with homicides a daily occurrence. Jobs, as it turned out, were in short supply. Many women resorted to prostitution to provide the sole income for their entire family. If there was one thing that the Amos n’ Andy show got right, it was the warning that Chicago wasn’t the paradise of golden opportunities that it appeared to be.

Hansberry’s parents occupied a place in Chicago society that most of its black migrants dreamed of reaching. Her mother, Nannie Louise Hansberry, was a school teacher and her father, Carl Hansberry, was a real-estate broker. They were educated, progressive, and protective. When they received Lorraine’s birth certificate they wasted no time in crossing out the world “negro” that was used to describe their daughter and replacing it with “Black.”

In 1937, her parents bought a house in a white upper class neighborhood at 6140 S. Rhodes Ave. It was illegal for blacks to purchase houses in white neighborhoods. The backlash was immediate. They were violently attacked day in and day out. Lorraine vividly remembered her mother walking around the house at night with a loaded German Luger. She took it upon herself to guard the lives of her family since nobody else would. Eventually, the neighbors sued to have the Hansberry family removed in the now famous case Hansberry v. Lee. Carl Hansberry worked closely with the NAACP and the case made it all the way to the Supreme Court.

Lorraine often commented on her father’s dogged quest for justice through the nation’s legal system. Carl Hansberry believed wholeheartedly that any person could achieve equality if they pursued it through the “proper” channels. He never even considered moving or backing down from the legal battle even while his family endured daily threats of bodily harm.

In an unpublished letter to the editor of the new York Times she wrote:

“My Father was typical of a generation of Negroes who believed that the “American Way” could successfully be made to work to democratize the United States. Thus, twenty-five years ago, he spent a small personal fortune, his considerable talents, and many years of this life fighting, in association with NAACP attorneys, Chicago’s “restrictive covenants” in one of the nation’s ugliest ghettoes …”

She goes on to write about how her family was bombarded by threats and outright violence for the duration of the case. They were traumatized day in and day out. Lorraine was cursed and spat at on her way to and from school. At one point the mob lobbed a “missile” into the house, nearly killing the then eight-year-old Lorraine.

On November 16, 1940, The Chicago Defender, the city’s only newspaper primarily for African-American readers, proclaimed on the front page “Hansberry Decision Opens 500 Homes to Race.” The court had overturned the decision and allowed the Hansberry family to remain in their home, thus freeing hundreds of thousands of black residents from the restrictions that kept them sequestered in dangerous, dilapidated areas.

The case took its toll on the whole family. Despite Carl Hansberry’s original optimism about the legal process, he became steadily more frustrated with the pervasive racism he encountered every day. A few years after his victory in court, he began making plans to move his family to Mexico. In 1946, he suffered a sudden cerebral hemorrhage and died. Lorraine often said that it was the court case that drove her father to an early grave.

Lorraine’s parents were Republicans, but Lorraine was more influenced by figures like W.E.B. Du Bois and Paul Robeson, both of whom were house guests during the court proceedings. She moved to New York City in 1950 to write for Robeson’s newspaper. Robeson and his publication both had a strongly Socialist tilt, which was one of the attracting elements for Lorraine. She left Chicago just in time to miss the Cicero race riot in the summer of 1951 when a mob of about 4,000 whites attacked an apartment building and local police allowed them to do over $20,000 in damage - around $200,000 today.

Instead, Hansberry began contributing to a widely-circulated Socialist paper right at the start of McCarthy era questioning. She saw her mentors, Du Bois and Robeson, be pestered, detained, and blacklisted for promoting “Communist propaganda.” Hansberry, however, passed unnoticed by those seeking to upset the paper’s foundations, mostly because she was a twenty-year-old unknown. But she wouldn’t fly under the radar for long.

Hansberry’s interests didn’t stop at the boarders of her country. She was an activist through and through. She covered stories about racism and lynchings, writing poems to express her rage and confusion, but she also worked on global struggles against imperialism and discrimination. She wrote in support of the Mau Mau uprising in Kenya, decrying the mainstream media for their bias. She demonstrated particular interest in Egypt where the recent revolution gave way to a flurry of feminist activity that rapidly propelled women to equal status in the country. Lorraine was also a vocal activist for gay rights, and is widely believed (with support from her personal notebooks) to have been a closeted lesbian. But in 1953, she married Jewish publisher, songwriter, and activist, Robert Nemiroff. After her death, Nemiroff published several of her unfinished manuscripts and finished her play “Les Blancs.”

In 1959, Hansberry’s first play, A Raisin in the Sun, premiered, and she became the first African American woman to author a Broadway play. Overnight she was propelled to the forefront of the black liberation movement. Her parents were unable to escape racism through legal means, so she was going to do so with the full force of black anger.

The play was a cultural event with the magnitude of an earthquake that funneled black audiences into theaters at incomparable rates. It united the thought processes and shaped the language used by black activists across the nation in the same way that Amos n’ Andy had implanted stereotypical images of blacks into the minds of white listeners. Even though it was projected to be a failure, the play was a windfall for Lorraine as well as for the black liberation movement.

In 1961, Hansberry authored two screenplays, but both were rejected by Columbia Pictures for being too controversial. The third draft more closely resembled the stage version and was approved. The original Broadway stars then reprised their roles on film with Sidney Poitier as Walter Lee Younger, Claudia McNeil as Lena, and Ruby Dee as Ruth. Lorraine became more influential on the national stage, and was instrumental in mobilizing blacks towards change. In 1964, Lorraine gave a speech at the Town Hall Forum where black activists and white liberals convened to share their thoughts. Charles Silberman, a white panelist, later wrote in a book, “When the struggle for Negro rights moves into the streets, the majority of [white] liberals are reluctant to move along with it. They are all for the Negroes’ objective, they say, but they cannot go along with the means.” Lorraine advocated for transforming the “white liberal” into an “American radical.”

During the forum, Lorraine was fighting another, more private battle against cancer. She soon became immobilized by the disease. Everyone gathered saw a fearless warrior, confident, and intellectually unyielding. However, at the same time Lorraine was wrestling with doubt. She wrote in her journal, “Do I remain a revolutionary? Intellectually - without a doubt. But am I prepared to give my body to the struggle or even my comforts? … Comfort has come to be its own corruption.” She resolved to travel to the South as soon as she felt better “to find out what kind of revolutionary I am.” She never made the trip. She died on January 12, 1965 at the age of 34.