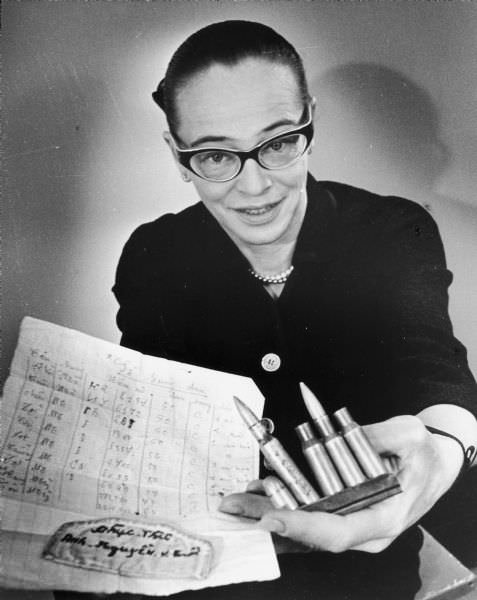

Dickey Chapelle

The Polite American with Tiger Blood in Her Veins

In 1961, Dickey Chapelle was the only female photojournalist parachuting into combat alongside U.S. troops. In fact, she was the first combat female journalist in U.S. history. Despite the jokes and, often, hate that swirled around the presence of a female on the battlefield, Chapelle always returned to the battlefield. Photography and record keeping were her passions and she pursued them single-mindedly.

Born Georgette Meyer in the Midwest, she was fascinated by aviation at a young age. She was consumed by a desire to reach for the sky. She was so enticed by the magic of flight that she adopted her nickname, Dickey, in honor of her hero, Admiral Richard E. Byrd. At age 14 she sold her first article to U.S. Air Service entitled, “Why We Want to Fly.” However, she also recalls that at the mention of her dreams, her mother exploded, saying, “No daughter of mine will ever set foot in an airplane!” (5). So, she settled for the next best thing. At 16 she enrolled in MIT with six other female students. (1)

She was determined to break barriers. She became the first woman correspondent accredited by the military in WWII. Then she lost that accreditation when she accompanied Marines onto Okinawa Island despite a ban on female correspondents going ashore in combat areas.

By 1945, she’d already written several books, primarily on aviation, and was working as an editor at Seventeen Magazine. She then married Tony Chapelle, a photography teacher who supported her writing by supplying the accompanying photos.

Dickie was unsatisfied with a quiet life and longed to return to foreign reporting. She and Tony began photographing the effects of war, and traveled to nearly two dozen countries as volunteer photographers for relief agencies and the State Department. By that time she was working as a publicist for Trans World Airlines in New York City and a research institute, but that didn’t stop her from traveling to Hungary to cover the revolution. (1)

In Hungary, she was held as a prisoner in solitary confinement for over a month. However, instead of being deterred by that experience, it invigorated her. After Tony funded her release, she began traveling from one conflict zone to another, photographically recording the events and thumbing her nose at the danger. Her presence in war zones was a curiosity as well as a revelation. There were very few women in journalism, and nearly none on the front lines. Many hailed perspective as revolutionary at the time. She even sold a book on military training to her editor after demonstrating the entire Army fitness test in his office. (1) However, others were aghast at the thought of a woman in a war zone. A general trend to officially ban women in 1967, but failed. (6)

In addition to covering war efforts, Dickey made records of human suffering around the world as well as the relief efforts she observed. In India she photographed a community development project to improve the lives of villagers. (1) Yet, it was her work in war zones that propelled her to wide recognition. She wrote about these conflicts with insight and grace.

“I had become an interpreter of violence. I’d covered three revolutions in three years - Hungary, Algeria, Lebanon … I minded the larger truths that the revolutions had failed. Hungary had fallen to the tanks. Brother still fought brother in Algeria. Rioting continued in Lebanon. But men continued to hope and fight for a better world”

In 1958, she was sent by The Reader’s Digest to cover the uprising against Fulgencio Batista in Cuba. Her report did not paint what she saw in Havana in a kind light:

“Around his empire of corruption, Batista build a secret police organization. The letters SIM and the sleek olive drab radio cars with submachine gun barrels poking through their windows appeared in the streets. Every police station in the large cities was said to have its own torture chamber. A fifty-year-old woman schoolteacher who during an interrogation had been violated with a soldering iron in Havana’s XII district, February 24, 1958, described the building. She said the chief’s office had walls of tile and drains int eh floor so it could be cleaned with a hose each day.”

Her tenacity in the face of danger and an apparent immunity to fear allowed her to face the atrocities head on. She did not shy away from any threat. So, using that fearlessness she and two other reporters, Herbert Matthews and Andrew St. George, secured an interview with Fidel Castro himself. Of that encounter she wrote:

"The emotional tension around him rarely lessened; he conveyed high pressure in every movement and was never still. His normal state of ease was a purposeful forty-inch stride forward, then back (it was nearly impossible to photograph him). His speaking voice was surprisingly soft and his incessant speech distinct. His manner of giving praise was a bear hug, his encouragement a heavy hand on the shoulder, his criticism an earthquake loss of temper. He reacted with Gargantuan anger to every report of dead and wounded; I considered this evidence that lie had never suffered the magnitude of losses Batista claimed.. The overwhelming fault in his character was plain for all to see even then. This was his inability to tolerate the absence of an enemy; he had to stand - or better, rant and shout-against some challenge every waking moment... In the rare times when he spoke quietly, Castro revealed a fine incisive mind utterly ill-matching the psychopathic temperament which subdued it."

Later, Fidel Castro would remember her as, “the polite little American with all that tiger blood in her veins.”

Dickey’s reporting was thorough and fearless, something that astonished many of her peers who underestimated her due to her sex. However, she was also never granted any special treatment. She once wrote to her publisher, “Not once has a general ever offered to trade me a SECRET operations order for my fair white virtue, and if it sounds as if I’m complaining, I guess in a sense I sure am.”

She titled her first book, “What’s a Woman Doing Here?” After the comment she most commonly heard on the battlefield. (1)

Her marriage deteriorated after Tony suffered from two heart attacks and decided to step back from reporting in favor of a quieter life. Dickey was not deterred. She had previously done all the writing while Tony took the pictures. Now, she took on both roles (1). After fifteen years of marriage she divorced Tony and officially changed her name to Dickey. However, she retained the surname Chapelle. (7)

Dickey was staunchly anti-communist, and so was compelled to volunteer her expertise in Vietnam. In early reports, she was highly sympathetic to the small numbers of U.S. troops that were attempting to defend the Ngo Dinh Diem administration (2), and argued for sending combat troops in. In 1964, After Lyndon B. Johnson sent in the first “official” US combat troop of 3,500 marines, Dickey became on of the few reporters (male or female) who went with the army on search and destroy missions. She still wholly supported the war effort, as did a majority of the U.S. public. An opinion poll conducted at the time reflected a whopping 80% support for sending in troops and conducting bombing raids in Vietnam. (2)

Earlier, in 1962 Chapelle made an astonishing discovery. Three separate marines approached her to say that she had photographed or interviewed their fathers in Iwo Jima and Okinawa two decades earlier. She wrote that she was in shock because, “I realized I was now covering my second generation of combat Marines - covering them, again, on embattled ground half a world away from home.” (1) And she continued to cover the war and those affected by it. Her impact was in recording the events that took place beyond the bounds that most journalists dared to cross - far from telegraph lines and Jeep-accessible roads.

The American public quickly became divided about the war. Dickie also became frustrated by the way her employer, National Geographic, was covering the war. In 1965, she wrote to her editors that she was aggravated to see that two weeklies had scooped her on a story about navel wars that she’d filed first. She went on, “Anyway I finally figured out something I could do about it. I just went to work for one of the weeklies.”

National Geographic was still sitting on one of her stories on November 4, 1965 when Dickey was covering the second day of Operation Black Ferret, a Marine search-and-destroy mission near the city of Chu Lai. It was nearly 8 a.m. when a lieutenant in front of her kicked a tripwire. A piece of shrapnel severed her carotid artery and she died soon after. (2) Fittingly, her last moments were captured in a photograph by Henri Huet. Her body was repatriated with an honor guard of six Marines and she was given a full Marine burial. (3)

Dickie Chapelle was the first of many war correspondent killed in Vietnam. However, her legacy goes far beyond a simple statistic. Chapelle wasn’t necessarily the best correspondent in the field. In fact, she was often harshly criticized by her editors for lacking professionalism and objectivity. Those criticisms were accurate. She entered the world of war correspondence completely unprepared. Yet, the rigors, both mental and physical, never deterred her. She dove in head first and tried to learn along the way. Sometimes she failed. Sometimes she provided insights that nobody else could. Indisputably, she paved the way for other women to follow in her footsteps.

-

(1) https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/world-photography-day-dickey-chapelle-female-war-photographer-combat-vietnam

(2) https://spartacus-educational.com/JFKchapelle.htm

(3) Ostroff, Roberta (February 11, 1992). Fire in the Wind: The Biography of Dickey Chapelle. Ballantine Books.

(4) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dickey_Chapelle

(5) https://narratively.com/female-photojournalist-war/#:~:text=Newsletters-,The%20Parachuting%20Female%20Photojournalist%20Who%20Dove%20Into%20War%20Headfirst,woman%20on%20the%20front%20lines.

(6) https://theglindafactor.com/dickey-chapelle/

(7) https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS3953

(8) https://dc.uwm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3389&context=etd